Spreading Awareness of Digital Preservation and Copyright via Omeka-based Projects

Alston Cobourn, Washington and Lee University

Through the use of Omeka, students discover why descriptive metadata matters and learn that the way files are treated affects their permanence.

Many primary, secondary, and undergraduate educators are aware of the open-source digital publishing platform Omeka and its uses as a tool for creating digital collections and exhibits in the classroom. As students use this platform, they can improve their understanding of the course material, learn soft skills used in effective collaboration, and become more comfortable with technology—all of which will help them throughout their academic and post-academic careers and daily lives. Additionally, all educators can use Omeka-based assignments to introduce students to many aspects of digital literacy.

First, Omeka provides numerous possibilities for demonstrating to students the characteristics and nature of digital files. The University Library at Washington and Lee began introducing Omeka to faculty as a possible pedagogical tool in the spring of 2015. My role as a librarian with archival training was to consult with faculty who wanted to integrate a digital humanities project into their course in order to determine if Omeka was the best tool for the project they had in mind and its intended goals. If Omeka was determined appropriate for a project, I provided introductory workshops to the class and additional support as needed.

By using Omeka, students learn that the way one treats those files affects their permanence, thereby introducing students to the concepts of fixity, authenticity, integrity, and renderability. Supporting each Omeka class project at Washington and Lee University required me to work with the professor to establish minimal level metadata guidelines appropriate for the materials that will be used in that particular project. Together we determined which Dublin Core (descriptive metadata) fields the students should use and created examples. After doing this for several classes, I’ve realized that it is more educational for the students if we share why this descriptive metadata matters, why their professor and I spent time thinking about these project-specific guidelines, and why consistency throughout the project is a best practice.

Yet an even better option would be for the professor and I to develop these guidelines with the students during a class session, walking them through the decision-making process, thereby using both my metadata expertise and the professor’s and students’ subject expertise. During this process I could explain what kind of information each metadata field is meant to record and then the professor and students could tell me which fields seem most applicable to the items they will be describing. After deciding which fields will be used, we could then discuss how to structure the information within the fields so that it is clear and complete. Going through this process with the students would allow us to emphasize that thoughtfully establishing metadata guidelines should be part of all scholarly digital projects. They learn firsthand that consistent metadata ensures that the finished project is understandable, useful, and sustainable.

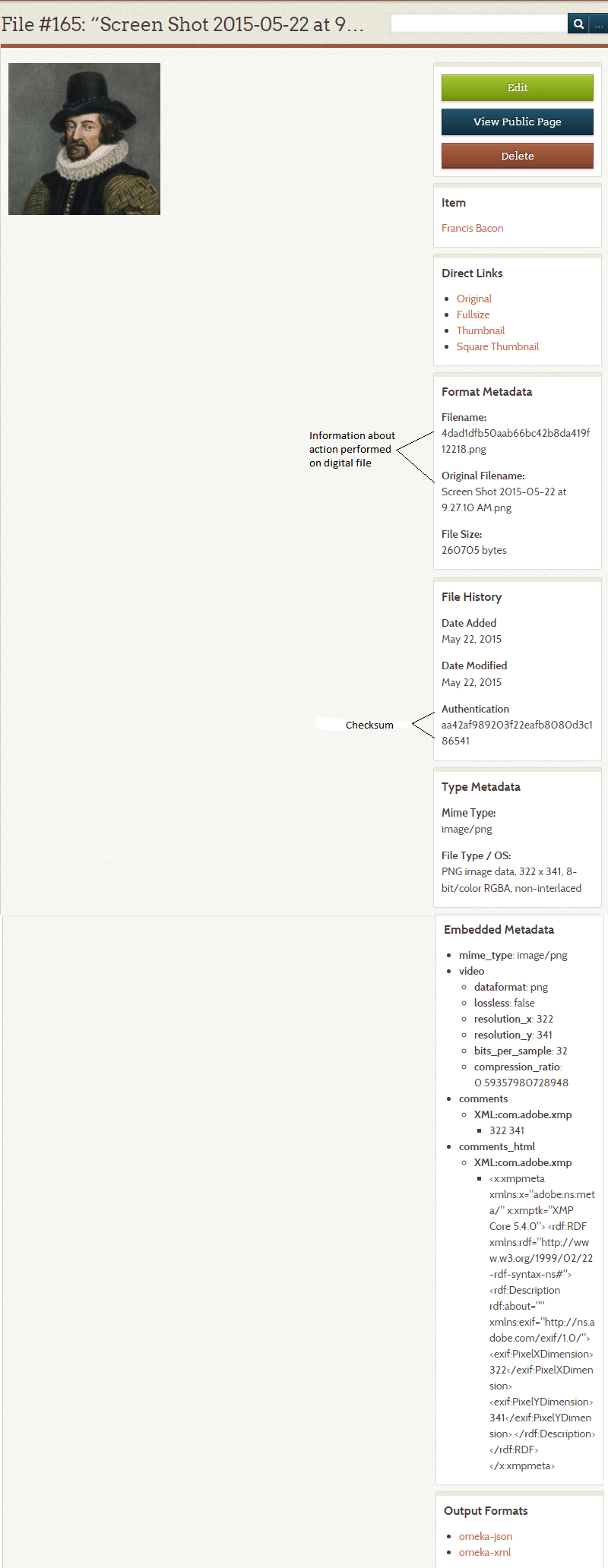

Before students begin uploading files into Omeka, instructors should work with a librarian or archivist colleague to develop a file naming convention. They should also help explain to students the benefits of such conventions, such as increased file stability and an enhanced ability to identify files. Once students have uploaded digital files (Fig. 1) and created the associated descriptive metadata (Fig. 2), the librarian or archivist can show them the preservation and administrative file metadata that is generated by and recorded in the system, which includes file size, date added, date modified, and checksum (Fig. 3).

There is also the opportunity to provide information about what happens to a file during compression, editing, and copying and how that affects long-term sustainability. Students can learn about differences among file formats, how to determine which one is most appropriate for their purpose, and why they should think about resolution and sizing when creating digital files for online projects. This knowledge will enable students throughout their lives to mindfully chose and/or create files in a way that best suits their needs and helps those files last. For example, every term students use the library’s poster printing service for class projects, and inevitably some discover post-printing that one of the images they used loses its detail when increased in size because its resolution and original size were too low to be suitable for this purpose.

A second aspect of digital literacy instructors can address through use of Omeka is copyright and licensing law. In order to create legal and ethical digital collections and/or exhibits with this software, students will need a basic understanding of these concepts and how they relate to web publishing and the scholarly communications cycle . This knowledge is required if they are to grow into responsible scholars who respect the intellectual efforts of others and understand their own rights as authors. Even when students are using materials that are not protected by copyrightthere is still an opportunity to explain why copyright is not a concern in that instance. This was the case in Professor Stephanie Stillo’s history course The 18th Century Search for the Blue Nile. Groups of students created Omeka exhibits around course themes. They primarily used photographs they took of the six volumes of James Bruce’s Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile housed in our university’s Special Collections and Archives department. They also used some supplementary images from internet sources, which were protected by copyright law.

When I am invited to a class to provide a tutorial on the mechanics of Omeka, I always ask the professor if I can also discuss copyright briefly. So far, I have found professors are happy to have me address this issue because they feel it is important, but they are not sure how to tackle it themselves. In the class session, I provide students with about 15-20 minutes of introductory information about copyright, public domain, fair use, and Creative Commons licensing, as well as links to charts and online tools. I share with them three web pages developed by librarians at Washington and Lee, Finding and Using Images, Finding and Using Audio, and Finding and Using Video. These sites discuss many aspects of digital literacy, including an introduction to finding freely available media.

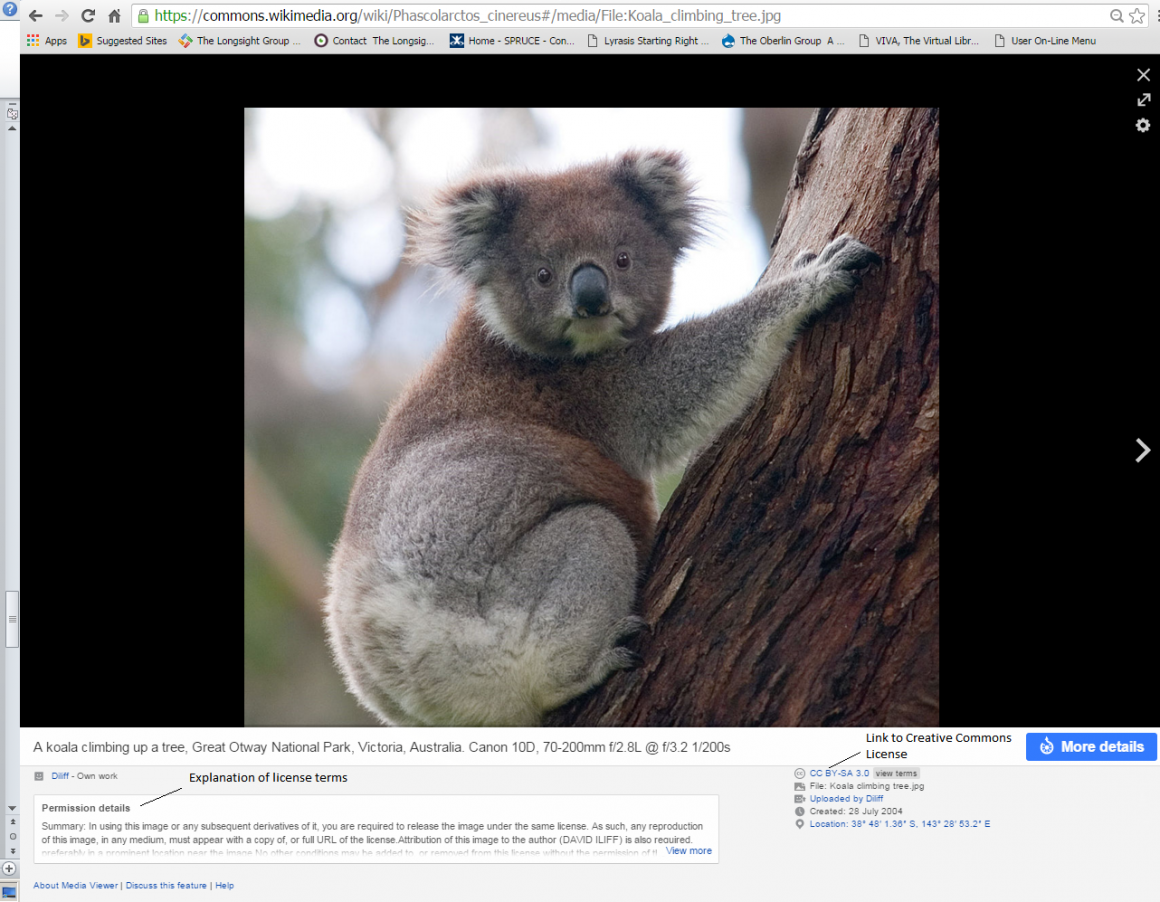

If the professor’s schedule allows, I then conduct one of several variations of an in-class exercise. Most frequently, I have students use a lab computer to search for an image, audio file, or video that could be useful for their project. Then as a group we assess whether the file is protected by copyright by interpreting any accompanying rights information, considering its age and, if applicable, date of publication, and conducting a fair use analysis if necessary. A second option is to have students do this individually, but since copyright and fair use are complicated topics, I opt for the group approach during their initial experience (See Appendix 1). Having students do such an assignment individually as follow-up homework is a good way to reinforce the day’s lessons. Alternately, I sometimes ask students to search for an image, audio, or video file via Creative Commons Search, and then we interpret the accompanying Creative Commons license as a group (Fig. 4).

Screenshot of a web browser containing a specific image found via Creative Commons Search and its associated licensing information

Engaging in discussion about intellectual property and digital media is especially important with this generation of students that have “grown up digital” because the ease of sharing information has greatly obscured the idea of information as a commodity. In each of the three classes I worked with on an Omeka-based project last spring term I asked the students if someone had talked with them about copyright during either high school or college. Two students answered yes. A third said she knew a little bit about copyright because her sister was currently in law school. 92.3% of the students I worked with had never received information about copyright during their academic careers..

Educators need not spend hours of their class time or derail their main course objectives covering digital preservation, copyright, and licensing, but all of us should seize the opportunities provided by Omeka-based assignments that work best within the situation’s limitations. Educators can easily scale which aspects they address to what seems feasible and most appropriate for the particular course. Providing education about digital preservation and copyright are essential aspects of teaching our students to be responsible information consumers and creators, which is part of our core mission to help them become lifelong learners. Engaging students with these issues for even a single class period will benefit them in the long term, and Omeka presents the perfect opportunity to do so.

Appendix 1

In-class Copyright Assignment

Version 1

- Have each student select an item (image, video, audio file) they could potentially use in their project. Have them use the Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States chart created by Peter B. Hirtle to assess whether or not the material is protected by copyright. If they are unsure of an item’s date of first publication, they should look at the dates they think are most likely and see how the copyright protection differs.If they determine the item is not protected by copyright, they are free to use it as they please! If they believe it is protected, they should move on to step II.

- Students should use the Fair Use Checklist created by the Regents of the University of Minnesota to go through a fair use analysis to assess whether or not they can legally use the item as they would like.

- Go around the room and have each student share their findings and reflections. Potentially, they could address these questions:

- What did you learn about copyright that you didn’t know before?

- What did you find confusing as you went through this exercise? Where did you have questions?

Version 2

Instead of having each student work through this exercise individually, have one student select a potential item and then lead the whole class through the exercise as a group. Ideally, repeat this exercise a couple more times with items selected by other students. This will ensure that the class has the opportunity to talk through several different situations.

Version 3

Ask students to individually search for an image, audio, or video file via Creative Commons Search and then write a paragraph interpreting the accompanying Creative Commons license. This assignment can also be done as a class with students sharing their interpretations verbally.

Alston Cobourn is an Assistant Professor and Digital Scholarship Librarian at Washington and Lee University where she specializes in digital preservation, archives and records management, and scholarly communications issues, including copyright and open access publishing. Alston previously worked with electronic resources management at North Carolina State University.

She holds a BA with majors in English and minors in Creative Writing and Journalism as well as a Masters of Library Science with a concentration in Archives and Records Management from UNC-Chapel Hill.

'Spreading Awareness of Digital Preservation and Copyright via Omeka-based Projects' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!